A Model Network

The Federation of Southern Cooperatives

Last fall, the Federation of Southern Cooperatives was awarded the Food Sovereignty prize, an alternative to Norman Borlaug’s World Food Prize that recognizes grassroots activists working for a more democratic food system. Upon accepting the prize, Federation Executive Director Cornelius Blanding said, “We believe all land matters, but we especially want to say black land matters. It matters to us in the South, it matters to our communities, it matters to this work, and it should matter to this world.”

“You had a lot of black farmers and landowners who experienced a lot of racism who formed cooperatives out of necessity.”

Early History – Cooperative Movement and Civil Rights Movement

The Federation grew out of what Blanding describes as “the Cooperative Movement colliding with the Civil Rights Movement.” Black-run collective economic organizations date back to before the Civil War. Leading up to and during the Civil Rights Movements blacks organized cooperatives and collectives as a way to build power and gain autonomy in the face of the white-run dominant economic structures, which often exploited and discriminated against blacks.

“You had a lot of black farmers and landowners who experienced a lot of racism who formed cooperatives out of necessity,” said Blanding

White-run businesses might refuse to sell blacks basic goods such as gas, or black farmers would be unable to sell their crops for a fair price. Marketing cooperatives gave farmers and crafters more power in the market place and credit unions and revolving loan funds kept more money in black hands and increased access to credit. Cooperatives also provided members with increased capital to buy land, factories, and equipment.

Recognizing the need to build on these early successes and advance the movement for black economic autonomy, in 1967, 22 cooperatives from 9 Southern states came together to form the Federation, an organization that would collectively support and advocate for black farmers and rural communities across the South through economic development, training, policy advocacy, and organizing.

The late 60s was a major period of growth for the Federation. Largely thanks to President Johnson’s War on Poverty and Great Society programs, the organization received significant funding, administered a number of rural economic development programs, and acquired the land base in Alabama that would eventually house their Rural Training and Research Center, still in operation today.

However, the organization faced numerous challenges in the 1970s, initially due to Nixon administration budget cuts and later, to a wide-sweeping FBI investigation on misuse of funding that consumed two years of the organization’s staff time and resources but ultimately came up empty-handed. To deal with this blow, the organization downsized, focused on their original goal of cooperative development, and created strategic collaborations with like-minded partners, including the Emergency Land Fund, with whom they eventually merged.

“Black farm land loss was happening at such an alarming rate, it was predicted by the US Civil Rights Commission in a 1965 report there would be no more black land by the year 2000. That forms the basis of the work we do, reversing that trend and saving black-owned land.”

Black Land Loss and Heirs Property

As land ownership is a critical piece of farm business stability and wealth building, land retention for African Americans and poor farmers has been a defining issue for the organization, and for dire reason. Between 1910 and 1997, farmland ownership among blacks plummeted from a peak of 15 million acres to just 2.3 million and the number of black farmers dropped from 218,000 to just 18,000, significantly outpacing the decline in the number of farmers overall.

“Black farm land loss was happening at such an alarming rate, it was predicted by the US Civil Rights Commission in a 1965 report there would be no more black land by the year 2000,” Blanding notes. “That forms the basis of the work we do, reversing that trend and saving black-owned land.”

The Federation identifies heirs property laws, the de facto legal process for passing land ownership to successive generations in the absence of a will or estate plan, as a major contributor to land loss. With heirs property laws increasing numbers of heirs have an increasingly smaller fractional (yet undivided) interest in the land over time. This situation and its accompanying legal complexity makes the land far more likely to be sold to an outside interest, usually not black.

Keeping Black Farmers Farming

The Federation also continues its cooperative development work. The Rural Training and Research Center provides trainings and technical assistance on cooperative development and recently hosted the 2014 CoopEcon Conference, organized in conjunction with Southern Grassroots Economic Project. The Federation’s five state-level offices also work on cooperative economic development and provide technical assistance to existing coops. In addition, the Federation has extended their cooperative development reach outside the U.S., assisting farmers in Haiti, Cuba, the Caribbean and Africa in developing cooperatives and providing farmer to farmer technical assistance.

The Federation’s Training Center also provides trainings in sustainable agriculture and programs for youth empowerment. The Center boasts a demonstration farm and is the site of a research station that the Alabama Land Grant Alliance (made up of the state’s three land grant institutions) maintains.

Policy Advocacy

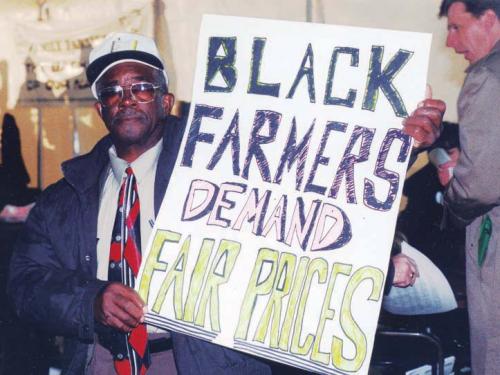

A primary issue for the organization is systematic and institutionalized racism historically engrained in USDA agencies and programs. Blacks and other minorities have long experienced discrimination and denied access to government loans, grants, and other support which has contributed to the decline in the number of minority farmers.

The Federation has focused its federal policy advocacy efforts on dismantling this racism by working to create policies in USDA that prioritize outreach and set aside funding for groups that have been historically underserved by the agency, including people of color, women, beginning farmers and veterans. The Federation was also instrumental in creating the Office of Advocacy and Outreach within USDA, which works to enhance access to USDA programs by historically underserved and socially disadvantaged groups, as well as a competitive grants program, the Section 2501 program, which has awarded millions of dollars in funding to organizations who assist socially disadvantaged and historically underserved farmers.

Another landmark victory was the settlement of the 1999 Pigford Class Action Lawsuit, filed against the USDA on charges of longstanding bias and discrimination against black farmers seeking to access USDA loans and assistance. The terms of the lawsuit’s settlement allowed those who experienced racism to file monetary claims of up to $62,500 ($50,000 and $12,500 to pay federal taxes). The USDA has paid nearly $1 billion dollars to more than 13,000 farmers, making this suit the largest civil rights settlement in U.S. history. The Federation worked with more than 2,000 farmers to help them file claims. The Federation has also worked on the subsequent lawsuits – Pigford II and the Hispanic and Women's Discrimination Settlement.

Built from the Ground Up

Like other successful networks, the Federation credits the strength and success of their organization to their grassroots leadership model. In his acceptance speech for the Food Sovereignty prize, Blanding describes the Federation as “a movement from the grassroots and directly from the people forming cooperatives out of necessity.”

This grassroots nature is built into the governance of the organization – each state organization has a board, and each state board has a representative on the Federation’s board. In addition, the cooperative members are voting members who all have a say in the organization’s direction. “Networks are truly built from the ground up and have to be built on need in order for them to be sustainable,” says Blanding.

Blanding also emphasizes both the importance and the challenge of prioritizing issues and focusing on them. “There’s a lot to be done and the challenge is in trying to figure out what to prioritize without spreading yourself too thin, especially with limited resources.”

Though the Federation has faced down significant obstacles in their half-century history, they’ve maintained a clear mission focused on cooperative economic development, land retention, and policy advocacy grounded in an unwavering vision of thriving black farmers and vibrant rural communities, and ultimately, of food sovereignty.

As Ben Burkett, the organization’s Mississippi State Coordinator puts it, “Everything we’re about is food sovereignty, the right of every individual on earth to wholesome food, clean water, clean air, clean land, and the self-determination of a local community to grow and do what they want.”

To learn more about the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, visit www.federationsoutherncoop.com

Photo Credit: Federation of Southern Cooperatives

This version of the article was updated on 1/8/16 at 11:44 am to correct factual inaccuracies.