A Model Network: The Niche Meat Processors Assistance Network

What is the right scale of processing needed to support small-scale and sustainable meat for the locavore market? As consumer demand for this kind of meat, called niche meat, grows, the seemingly obvious conclusion is the need for more processing facilities has also grown. But for many reasons, this question is more complicated than it first appears, and the true answer requires bringing both livestock farmers and meat processors to the table.

The Problem: The Plant is not the Market

Over her 15 years of working in the realm of sustainable and local meat and meat processing, Gwin has come to learn why the “as-needed” part is so complex. As a graduate student at UC Berkeley, Gwin was examining how to scale up sustainable agriculture, using beef production in California as a case study. She spent a lot of time talking to ranchers producing for the niche market and heard frequently their frustrations over how difficult it was to get their products processed.

But she was also talking to processors, and learning more about the challenges facing that industry. Processing plants, even small ones, are very expensive pieces of infrastructure to build and maintain. If processors don’t have enough product coming in from livestock farmers to justify the cost of the plant, called throughput, it’s not feasible for them to stay in business.

Convincing livestock producers to quantify their market demand can be a hard sell, though, because in order to create demand to justify building a facility, producers have to potentially drive far away to find a facility to process their meat before they can sell it and test out the market. Even so, the money a producer will spend to test their market is far less than the cost of building the infrastructure.

“A new plant should not be built based on the generalized view that consumers will pay 10 – 15% more for meat that is branded as local and sustainable,” said Gwin. Producers must ensure that there is consistent and reliable demand for their product. Without that demand facilities will, and do, fail.

“The plant is not your market. You have to build your market, which means there needs to be throughput and buyers.”

“The plant is not your market,” Gwin continued. “You have to build your market, which means there needs to be throughput and buyers.”

Thistlethwaite, who first learned of NMPAN when she was running a pastured pork and egg farm in California, added, “Farmers don’t often see or value the role that processors play. They think of them more as the relationship they have with their barber, when they need to think of them as the general contractor they would hire to build their house. This is the key aspect of their business. It needs to be more of a commitment. Processors are in the business of service to the farmers, if they’re a slaughterhouse that works with independent producers. If they’re not communicating with farmers and their needs, they shouldn’t be in that business.”

Hooking People into the Same Conversation

Gwin realized that producers and processors didn’t understand each other’s business because they weren’t talking to each other, and they needed to be. So she began connecting the ones she knew in California to discuss what was working and what wasn’t, and to better understand each other’s needs and industries.

A few years later, she attended a conference and heard stories from other parts of the country about producers who couldn’t find processors and processing facilities that were failing. She decided to expand her network nationally, with the help of another researcher at Iowa State, Arion Thiboumery (now a managing partner at Vermont Packinghouse.) They launched the concept in 2008 at a conference organized by the USDA Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education program (SARE), and received funding to build out their network. They launched a website and newsletter, established a listserv, and started offering learning opportunities through webinars and print educational resources. The network also created a peer learning initiative that pairs experienced network participants to those new to the field, and developed a network of state affiliates that have expertise on state-specific issues.

Network Convenor to Thought Leader

"Farmers don’t often see or value the role that processors play. They think of them more as the relationship they have with their barber, when they need to think of them as the general contractor they would hire to build their house. "

In 2011, then Deputy Secretary of Agriculture at USDA, Kathleen Merrigan, directed USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) to write a report on the state of processing infrastructure for locally sourced meat. ERS approached NMPAN to write the report, published in 2012. This was a turning point for the network, where their role grew beyond hosting a space for people to have discussions to really leading the thinking on what needs to be done to support the niche meat industry. Since then, NMPAN has published several more reports and articles for USDA and scholarly journals.

In addition, they provide technical assistance and expertise on policy impacting the niche meat sector to USDA. They were recently tapped by USDA to do an analysis of the agency’s past decade of investment in meat processing, to inform how they allocate money in the future. They also connect producers and processors in their network to USDA when the agency is looking for input on regulatory development.

NMPAN also works with policy advocacy organizations (such as the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition) to advise on policy changes that will address challenges and support producers and processors. For example, NMPAN is currently advising NSAC on policy proposals related to support for local and regional meat processors that NSAC will include in marker bills for the next Farm Bill.

Challenges

“People think we’re negative. They tell us, ‘You guys are just downers,’” said Gwin. “We don’t want to be in the position of always saying, ‘No, no, no, this doesn’t work.’ But the problem is that, over the years, we have seen so many plant projects start and not work out that we start to become a little disgruntled. And I know we’re not always as optimistic as people would like us to be. It is absolutely possible for a small-scale, USDA inspected plant to succeed – we know many such operators – but it is very challenging.”

Gwin had a watershed moment a few years ago when an organization asked her guidance, and she told them what she thought based on what she had seen in other places. The organization thanked her but did not take her advice and built a plant that ultimately wound up failing.

“I realized it was not my job to keep people from making bad investments,” Gwin continued. “It’s more that you do want people to try things in as informed and prepared a way as possible, and it breaks your heart to hear about a group of producers who get together and sink a bunch of money into something that doesn’t pan out for them.”

Thistlethwaite added, “We can’t blame ourselves if a business doesn’t succeed. It takes a lot to get new businesses off the ground and keep them viable. Processing is a low-margin business and you have to run it really tightly. We just have to encourage people to learn and use best practices. We don’t want to scare away every entrepreneur out there who is thinking about doing this.”

Advancing the Conversation

Gwin and Thistlethwaite believe that NMPAN has advanced the thinking around niche meat processing and increased the understanding among both producers and processors about what the other needs to stay viable.

“I think that simply creating the space where this conversation can happen is a major accomplishment. There have been times when the listserv conversation can be hot, and one sector has wanted a spinoff listserv. But if we spin you off, if you’re not talking up and down the value chain, then what is the point of NMPAN?

"producers [Have told] me, ‘I have learned so much about processing that I am not the dunce I used to be. I know what questions to ask and I am a better customer.’”

“The kind of feedback I get from people ranges from, ‘Wow you provided us with a key piece of information for us to make a really good decision for our business,’ to producers telling me, ‘I have learned so much about processing that I am not the dunce I used to be. I know what questions to ask and I am a better customer.’ Or it could be an NGO that wants to work on local meat, and says, ‘We want you to come out and talk to us about local processing.’ We start talking and we realize processing is not the issue and they make way more progress on the real issue that they need to focus on.”

As a network that prides itself on expanding and deepening the conversation between stakeholders who might not otherwise be connected, Gwin feels that NMPAN’s peer learning component is responsible for many successes she never hears about.

Added Thistlethwaite, “That’s what I love about this network: getting people to talk in both directions, and realize that interdependency on each other is critical to each other’s success.”

To learn more about NMPAN, visit www.nichemeatprocessing.org.

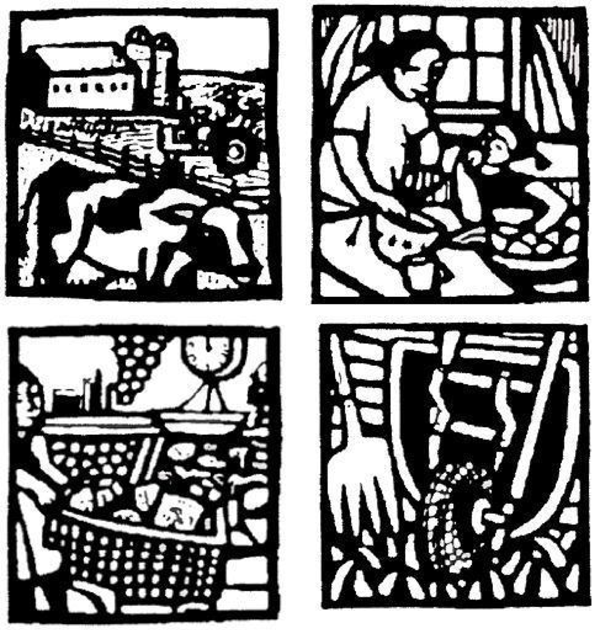

Photo Credit: NMPAN